It’s a simple question that we do not often hear from advisors to taxable ultra-high-net-worth individuals when discussing investment opportunities. Projected tax liabilities from investments can be challenging to compute up front when considering an investment, may not be the same from client to client and may not be intuitive or easy to explain. Many advisors throw up their hands, and since the norm is to consider investment returns on a pre-tax basis, and that is how “everyone thinks”, why buck the trend?

We have noted in prior articles and papers that assessing taxes and their impact on investment returns is critical for properly advising clients and managing their portfolios to amplify the accumulation of long-term wealth. Yet, the investment industry is inconsistent in its definition of tax-adjusted returns, tax alpha and similar concepts (if they are addressed at all).

Measuring what Clients Actually Keep

A deeper analytical approach is needed to define various return metrics in tax-efficient investing. The objective is to provide a “common yardstick” for measuring returns for investments with varying degrees of tax efficiency and comparing them to non-tax-efficient investments. The methods may be used across the investment spectrum, from public stocks/bonds to private markets (private equity, private credit, real estate, infrastructure, etc.).

Start with the well-known concept of gross returns. In private markets, we use internal rate of return (“IRR”) as one of the standard performance metrics. Now subtract all of the fees associated with the investment (e.g., transaction costs, sponsor management fees/carried interest, advisor fees, etc.) and recompute performance. We call this Gross Net of Fees (“GNOF”) IRR, or just Net IRR.

What about other leakage items, such as taxes? Like fees, taxes also reduce the end cash flows available to investors. We define the concept of After-Tax Returns (“ATR”) as the performance after removing fees (to get to GNOF), and then subsequently removing taxes (to get to ATR). After-tax returns more accurately reflect what an investor keeps from their investments. Just as GNOF provides a consistent way for investors to assess investment returns after fees, ATR provides a consistent way to measure investments after both fees and taxes.

Defining Tax Alpha

If no special tax alleviation strategies are used, the ATR equals an investor’s Fully Taxed Return (“FTR”). However, not all investment strategies are created equal in terms of tax efficiency. Certain investments in private markets may utilize tax incentive programs enacted into law to provide investors with extra incentives – for example, bonus depreciation on real assets, opportunity zones, investment tax credits on renewable energy projects, etc. We call this Tax Benefit Harvesting, whereby an investor purposefully “harvests” benefits available under the tax code to eliminate or defer taxes that would otherwise be due. In public market investing, tax loss harvesting works in a similar fashion. The tax benefits produced by tax-advantaged investment strategies may result in an after-tax return higher than the fully taxed return.

One final concept is needed before we lay out some numbers. The tax savings (extra cashflows) that one may generate by employing the tax advantaged strategies mentioned above (i.e., the difference in the cashflows between ATR and FTR) is the incremental benefit that you as an astute tax-aware investor (or advisor) have produced over and above a standard investment. Add those cash flow savings to your GNOF, and you have a Tax Adjusted Return (“TAR”) that is above the GNOF. That extra performance, or the difference in IRR between TAR and GNOF, is the Tax Alpha, and is typically quoted in basis points (“bps”) of extra performance generated by tax-advantaged investment strategies. TAR is easy to understand – if an investment’s Net IRR is 15%, and my tax savings generate a Tax Alpha of 200 bps (+2%), my Tax Adjusted Return is 17%. TAR is a “common yardstick” that can be used to evaluate investments relative to each other.

What the Numbers Show

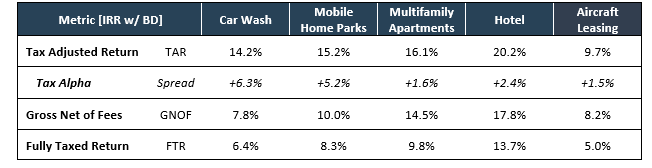

Now, let’s look at some IRR numbers for some hypothetical private markets deals that use bonus depreciation (“BD”, a real assets tax advantaged strategy) to defer taxes to assess the power of this method, with the assumption that the investor has substantial pending tax liabilities:

Right away, a few things should jump out from this table. First, what if the investor was looking at a car wash investment, and failed to consider the use of bonus depreciation or the impact of taxes on this investment, that investor might think that the returns are pedestrian. But tack on +630 bps of Tax Alpha, and that investment looks substantially more compelling. Second, when married to the same tax-advantaged investment program, different types of investments can produce significantly different Tax Alpha. Third, the “common yardstick” of TAR should be apparent. Suppose the investor was looking at the Gross Net of Fees return, and the Car Wash and the Aircraft Leasing investment had about the same risk. In that case, one might choose the Aircraft Leasing deal (ignoring portfolio effects, correlation, etc.). But on a TAR basis, the Car Wash looks much more compelling on an as-underwritten basis.

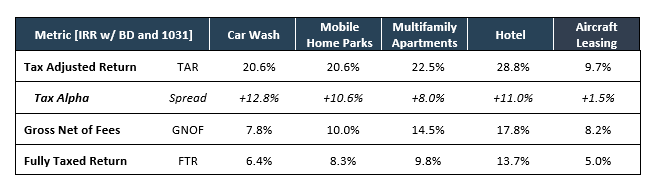

Finally, we note that private markets’ tax mitigation strategies can often be “stacked”—that is, multiple tax incentive programs can be used for the same investment. Take, for example, 1031 exchanges used in real estate deals to rapidly reinvest sales proceeds to buy another asset and defer paying capital gains taxes at the date of sale. If we use bonus depreciation at the beginning of the investment, and then a 1031 exchange when the property is sold, our table adjusts to the following:

These are substantial improvements to returns, and those improvements (i.e., tax savings) are retained in the investor’s portfolio, which can then be reinvested to generate additional compounding returns.

Ultimately, investment decisions may be made with greater analytical rigor using the tools described herein to understand actual after-tax dollars retained by investors.

#Whats #TaxAdjusted #Return