Charles Ellis’s seminal work, Winning the Loser’s Game, published in 1998, highlighted a sobering reality for investors: only about 20% of actively managed funds—those attempting to beat the market through security selection or market timing—were able to generate a statistically significant alpha, and that was before factoring in taxes. For taxable investors, taxes often exceed both expense ratios and trading costs, further eroding any outperformance. Ellis concluded that active management is a “loser’s game”—winnable in theory, but with odds so poor that the rational choice is not to play. Instead, he advocated for systematically managed vehicles like index funds, where the odds are stacked in the investor’s favor.

The Odds Have Gotten Even Worse

Since Ellis’s original analysis, the landscape for active management has only grown more challenging. As detailed in my book, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha, co-authored by Andrew Berkin, the proportion of actively managed funds delivering statistically significant alpha has now dropped below 2%. Several structural trends explain this persistent decline:

-

Academic research has transformed alpha into beta: What was once considered manager skill is now often explained by exposure to systematic risk factors.

-

The pool of less-informed investors (“victims”) has shrunk: As markets have become more professionalized, there are fewer easy targets.

-

Competition has intensified: The rise of sophisticated institutional investors has made it harder for anyone to gain an edge.

-

More dollars are chasing alpha: Increased competition for a shrinking pool of opportunities dilutes potential outperformance.

SPIVA 2024: The Scorecard Doesn’t Lie

The S&P Dow Jones Indices SPIVA Scorecard, the industry standard for benchmarking active versus passive performance, delivers a damning verdict on active management. Among the key findings:

Over 20-year period 2005-2024, 94.1% of all domestic funds underperformed the S&P 1500 Composite Index. And of the 18 domestic fund categories (including variations of large, mid, small, value, growth, and real estate), in only two categories did less than 90% of the funds underperform their benchmark. The “best” category was large value funds were 87.8% of funds underperformed.

On a risk-adjusted basis the performance was even worse, with 97.3% of domestic funds underperforming the S&P 1500 Composite Index. Less than one-half (48.5%) of domestic funds even survived the full 20-year period.

On an equal- (asset-) weighted basis, domestic funds underperformed the 1500 Composite Index by 2.28% (1.37%).

In case you believe the propaganda that the market for small caps is less efficient, on an equal- (asset-weighted) basis small growth funds underperformed the S&P 600 SmallCap Growth Index by 1.7% (0.65%), small-cap core funds underperformed the S&P 600 SmallCap Index by 1.79% (1.05%), and small value funds underperformed the S&P 600 SmallCap Value Index by 1.23% (0.41%). Further, n an equal- (asset-) weighted basis REIT funds underperformed their S&P REIT benchmark by 1.8% (1.28%).

The international evidence was just as compelling.

Over the 20-year period, 95.4% of emerging market funds underperformed the S&P/IFCI Composite Index and 73.2% of international small-cap funds underperformed their benchmark (the S&P Developed Ex-US SmallCap Index). On a risk-adjusted basis the performance was even worse, as 96.9% of emerging market funds underperformed and 75.6% of international small-cap funds underperformed.

Over the last 15-year period, 92.5% of global funds underperformed the S&P World Index, and 88.3% of international funds underperformed their benchmark (S&P World ex-US Index). On a risk-adjusted basis the performance was even worse, as 97.5% of global funds underperformed and 89.2% of international funds underperformed.

Over the 15-year period, on an equal- (asset-) weighted basis global active funds underperformed by 2.65% (1.63%) and international funds by 1.12% (0.32%).

Over the 20-year period, on an equal-weighted basis international small funds underperformed by 0.25%. However, on an asset-weighted they outperformed by 0.34%—the single case of outperformance. Emerging market funds did not fare as well as they underperformed by 1.79% on an equal-weighted basis and by 0.89% on a value-weighted basis.

The evidence was also compelling when it came to fixed income managers.

In the seven categories (general investment grade, intermediate investment grade, high yield, mortgage-backed, inflation linked, emerging markets, and global income) where 20-year data was available, the percentage of underperformers ranged from 79.3% (global income funds) to 95.8% (Inflation-linked funds).

Over the last 15 years a full 100% of loan participation funds underperformed their benchmark index and 96.4% of government short and short-intermediate funds underperformed. In none of the other seven categories did a majority outperform.

And for taxable investors, it is important to remember that all of the above figures are based on pre-tax returns.

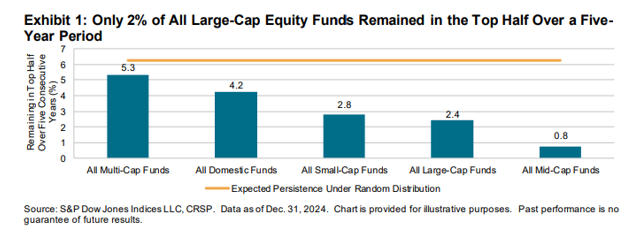

Persistence: Luck, Not Skill

S&P’s 2024 Persistence Scorecard underscores the fleeting nature of outperformance. In every category, the persistence of top-quartile performance was less than what would be expected by chance, reinforcing that past success is a poor predictor of future results.

The Virtuous Circle of Passive Investing

For investors, the implications are clear. The relentless competition among providers of passively managed funds—those constructed using transparent, evidence-based rules—has driven costs to unprecedented lows. Today, investors can access broad-market index funds with expense ratios in the single digits, or even zero, as with the Fidelity ZERO Total Market Index (FZROX).

This downward pressure on fees is making passive investing even more advantageous, creating a virtuous circle: lower costs attract more investors to passive strategies, which in turn shrinks the pool of less-informed investors that active managers can exploit, making it even harder to generate alpha.

Key Takeaway

The data is unequivocal: active management’s persistent failure is not a temporary phenomenon, but a structural reality. For investors, the prudent path remains clear—embrace low-cost, systematically managed funds and let the odds work in your favor.

Finally, the trend to lower expenses is making passive investing even more of a winner’s game. And that is contributing to a virtuous circle—lower costs are helping drive more investors to become passive, shrinking the pool of victims that can be exploited and raising the hurdles for the generation of alpha.

#Active #Managements #Persistent #Failure #Perspective