Interest rates impact every investment so we keep tabs on all things related to the Federal Reserve. The forward Fed appears to be quite different from the Fed of recent years, so this article will discuss the economics behind the potential new Fed ideology. One can never fully predict interest rates, but a greater level of understanding increases one’s odds of getting the direction right.

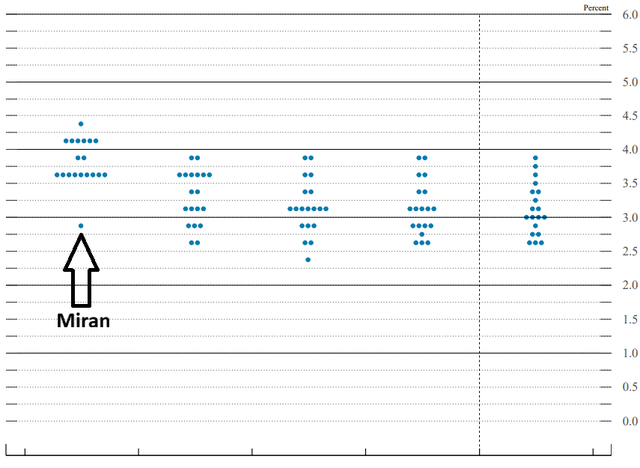

Miran is an outlier, but maybe not for long

The newest Fed appointee, Stephen Miran, arrived with a bang, calling for a 50 basis point cut and being a true outlier on the dot plot. His projection for the midpoint of the Fed Funds Target range at the end of 2025 is fully 75 basis points below the majority.

FOMC, annotation added

With Powell’s term ending in May and the lingering possibility of Lisa Cook being removed, there could be up to 2 more like-minded individuals joining the Fed, one of whom could be in the chair position.

Thus, it behooves us as investors not to dismiss Miran as an outlier but rather to study his methodology as it could have an increasingly large impact on the Fed.

Those who follow my work know that I prefer middle of the range interest rates and believe a 10-year Treasury floating somewhere in the vicinity of 3%-4.5% is healthiest for the economy. As such, I do not necessarily welcome the idea of a radically lower Fed Funds rate, but it is still worth understanding the economic ideas behind it.

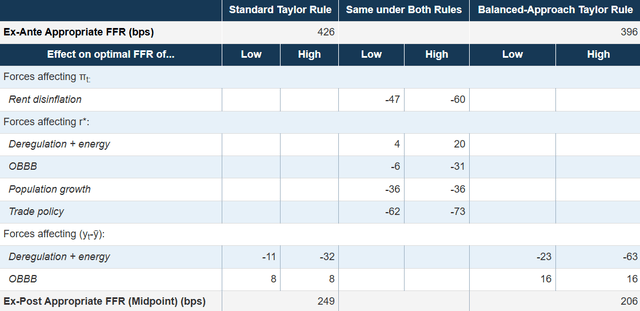

On September 22nd, Miran gave a very detailed speech at the New York Economic Club which revealed quite a bit about his differing perspective on rates. Specifically, his views diverge on inflation, R* and the economic output gap. These are summed in the table below and then we will discuss the economic concepts behind them.

Federal Reserve

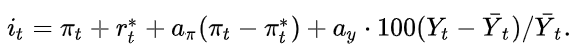

Miran expressed his fondness for the concept of the Taylor rule which he believes in using to inform but not dictate decisions. The Taylor rule formula looks intimidating, but most of the difficulty is in the notation with the underlying concepts being rather straightforward.

We will reference the Taylor rule as notated on Wikipedia because it uses the same notation as Miran’s table above.

Wikipedia, Taylor Rule

In plain English, this says:

The Fed Funds Target Rate equals inflation plus the equilibrating real interest rate and then 2 adjustments for actual inflation relative to target inflation and actual output relative to potential output.

Miran suggests that inflation is actually lower than what is currently being measured by the Fed.

“Because measured inflation incorporates rental inflation with a lag, it has remained elevated above market rents for several years, infamously “catching up.” While an index of all-tenant rents took time to incorporate the spike in new rents in 2021 and 2022, that gap subsequently closed, indicating the catch-up is complete. Now, new rent indices show this inflation is well below all-tenant inflation, around 1 percent annualized. Rents for all tenants will fall toward this low rate as people moving or renewing leases sign at current market rates, and I expect CPI rent inflation will decline from its current level of roughly 3.5 percent to below 1.5 percent in 2027. This implies a roughly 0.3 percentage point decline in total PCE inflation; by early 2028, I expect that effect to grow to a 0.4 percentage point decline. Per a Taylor rule, that works out to an appropriate fed funds rate roughly half a percentage point lower than current shelter inflation would imply.”

The lag in how rental inflation is recorded has been discussed by many, including Jeremy Siegel. As we observe the rental rates of apartment REITs, it is clear that rents are basically flat year-over-year, so I do think there is truth to the standard measure of rental inflation being significantly lagged.

Using a more current number for rental inflation, Miran thinks inflation is about 40 basis points lower than the Fed’s number, which would imply a 50 basis point lower Fed Funds target rate per the Taylor rule.

The majority of Miran’s adjustments are to R* itself. As a reminder, R* is the equilibrant real interest rate – essentially the interest rate in excess of inflation that the market demands on short-term capital.

R* is a necessary concept that seemingly every Fed official uses, but at the same time, it is unobservable and thus somewhat nebulous. Inflation gap and output gap can be largely measured so it is easier to base policy on those using a somewhat constant R*. In recent years, the Fed has been somewhat hesitant to make adjustments directly to R*.

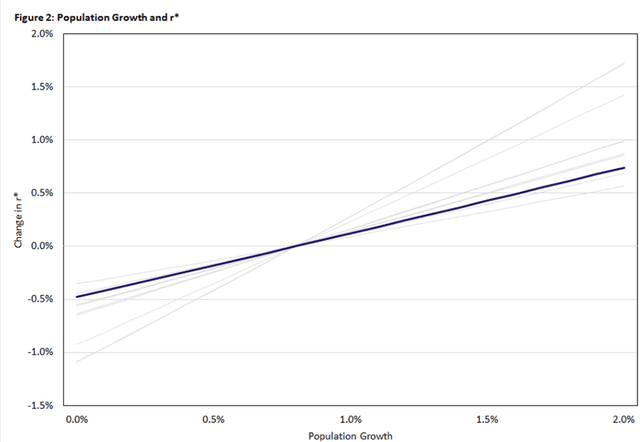

However, there is precedent for it. A 2016 Fed paper discusses some of the macro factors that impact R* with one of the largest being population. Per the Fed paper:

“We find that demographic factors alone can account for a 1.25 –percentage-point decline in the equilibrium real interest rate in the model since 1980. [ ] The model is also consistent with demographics having lowered real GDP growth 1.25 percentage points since 1980, primarily through lower growth in the labor supply”.

It is worth noting that this paper was written during a time of Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) and may have been part of the justification for ZIRP.

The Fed proposes 2 reasons why higher population growth leads to higher R*

“Younger workers are more productive, thus increasing the returns from capital.

The expectation of a growing population leads firms to invest in more capital in anticipation of a larger workforce to utilize this capital for production.”

The basic outcome of the model is that the lower the population growth, the lower R* should be.

Richmond Fed

Miran is applying this model to the current situation, which is a substantially tighter immigration policy. He estimates that the changed immigration policy will lower population growth from 1% annually to 0.4%. Translating this into R* he says:

“A 1 percentage point drop in annual population growth can reduce r* by 0.6 percentage point. So, the expected decline in U.S. population growth equates to a nearly 0.4 percentage point drop in the neutral fed funds rate.”

His numbers appear to be roughly in line with the model posted above.

Miran’s largest deviation from the rest of the Fed

Miran’s largest point of differentiation from other Fed officials seems to be on how he views tariffs.

Most of the Fed is accounting for tariffs as an inflationary force which shows up in their estimates of inflation for the remainder of 2025 and 2026. So for them, tariffs are not impacting R* but since the Fed Funds target rate is some composite of inflation and R*, the net result is that most of the Fed are targeting a higher rate as a result of tariffs.

Miran has 2 views on tariffs that differ from the majority:

- He does not see tariffs as materially inflationary

- He sees the revenue side of tariffs as reducing R*

Per his speech:

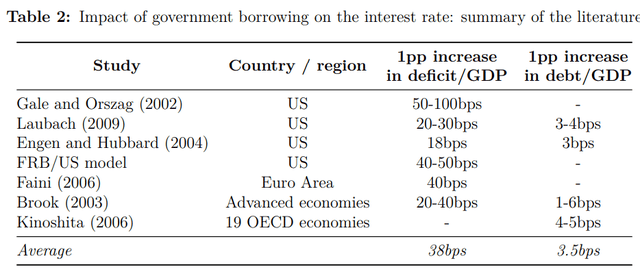

“The Congressional Budget Office estimates tariff revenue could reduce the federal budget deficit by over $380 billion per year over the coming decade. This is a significant swing in the supply–demand balance for loanable funds, as national borrowing declines by a comparable amount. A 1 percentage point change in the deficit-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio moves r* by nearly four tenths of a percentage point, according to the average of estimates summarized by Rachel and Summers. This 1.3 percent of GDP change in national saving reduces the neutral rate by half a percentage point.”

The concept that lower deficit-to-GDP reduces R* makes sense to me directionally. It essentially improves the credit of the government so the demanded interest rate would be lower.

As for the magnitude of impact, Miran seems to be basing it on this historical data/model, which was cited in his speech.

Rachel & Summers

The revenue from tariffs is quite easily measured on a backward basis. Forward tariff revenue is a bit harder to calculate as tariffs may cause behavioral spending shifts.

Similarly, we will not know the inflationary impacts of tariffs until more data comes out.

As time reveals more data on each point, the gap between Miran and the other Fed officials will likely close over time. It is just unknown at this point in which direction it will close.

Summing up the forward Fed

Miran’s approach emphasizes changes to R* itself which was previously a largely untouched figure. Most of the adjustments Miran makes to R* are in the negative direction, meaning a lower equilibrant real interest rate.

To the extent Miran persuades other Fed officials of his methodology or other like-minded individuals simply join the Fed via future appointments, I would anticipate a general downward movement of the Fed Funds rate.

Interest rate movements impact just about every financial instrument but some stand to benefit far more than others. In a follow-up article, we will discuss the individual securities we believe are best positioned for the environment.

#Analyzing #Direction #Federal #Reserve